Most grammar teachers will almost immediately recognize this style of diagram. Some will smile, but some will roll their eyes! There’s seldom anything in between.

Somewhere along the way (circa 2015), while at the Farmington County Club (aka Farmington Correctional Center) I stumbled on an old grammar book from the 70s, which was still using an old 19th-century system for diagramming sentences. This system came to be known as the Reed-Kellogg system for sentence diagramming.

“Most methods of diagramming in pedagogy are based on the work of Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg. Some teachers continue to use the Reed–Kellogg system in teaching grammar, but others have discouraged it in favor of more modern tree diagrams.”

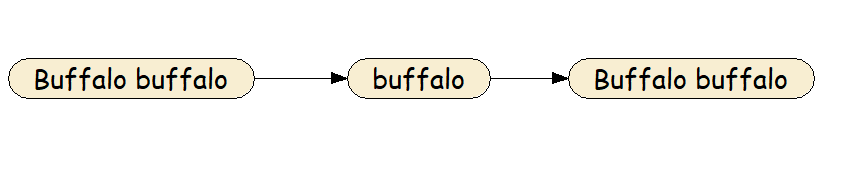

That’s not quite right. “They” have discouraged it - or tended to ignore it - and as far as I am aware, the modern tree diagrams are largely confined to university linguistics departments. No one does this in high school:

But my guess is that this “scientific” approach in the 60s (Noam Chomsky among others) is probably what actually killed the Reed-Kellogg system which turned out to be a pre-cursor.

Reed and Kellogg were writing in the 1870s, but the system goes further back at least to 1847. All this is nicely and meticulously documented here:

Systems Competing with Reed-Kellogg

We know little about it today but I can dimly imagine the forgotten wars of competing diagrams in the 1890s! Grammar teachers are familiar with Reed-Kellogg only because they “won” that war. As they say, the winners diagram history … their way!

In an earlier system in 1847, Clark began his textbook this way …

But the Reed-Kellogg system would diagram it thus …

But arguably a better system would do this …

That’s the way I do it. One can argue about which way the arrows should go, but the reading is fairly intuitive. Obviously, in the beginning, something was caused to happen. In fact, two things. The Heavens above and the Earth below! (You could actually get rid of “and” altogether if you like.)

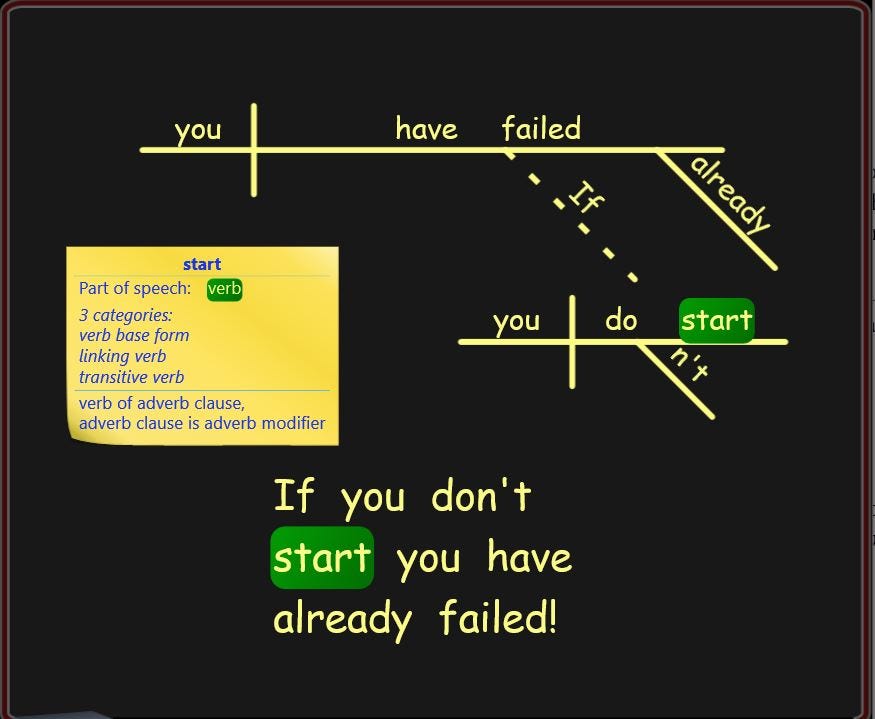

But diagramming sentences is a “fading art” they say. According to NPR, here’s one version of the opening line of Kafka’s Metamorphosis:

A Picture of Language: the Fading Art of Diagramming Sentences ...

Burns Florey and other experts trace the origin of diagramming sentences back to 1877 and two professors at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. In their book, Higher Lessons in English, Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg made the case that students would learn better how to structure sentences if they could see them drawn as graphic structures.

After Reed and Kellogg published their book, the practice of diagramming sentences had something of a Golden Age in American schools.

"It was a purely American phenomenon," Burns Florey says. "It was invented in Brooklyn, it swept across this country like crazy and became really popular for 50 or 60 years and then began to die away."

By the 1960s, new research dumped criticism on the practice.

"Diagramming sentences ... teaches nothing beyond the ability to diagram," declared the 1960 Encyclopedia of Educational Research."

So writes NPR. Two things: First, I hate to have to fact-check NPR (of all places!) but I have to. It goes back at least 30 years before. Indeed, “in the beginning” was the opening sentence diagram of that much earlier book as printed above. (So much for '“experts” and for NPR).

Second: what does this mean really? Imagine saying "doing algebra ... teaches nothing beyond the ability to do algebra"! Well ... yes ... but you need to prove that ability is without benefit whatsoever ... which is just assumed and is essentially begging the question. I’ve decided to revisit this question.

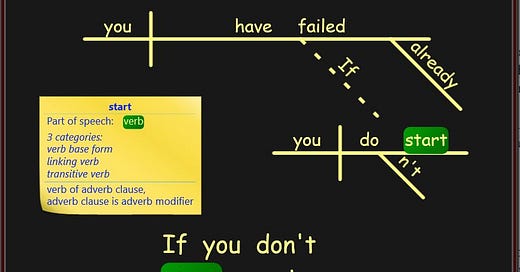

Can we do better? As Rabbi Moshe D. Bryski once said, “Yes, we can”1:

Fact-checking NPR again: some translate that last bit “into a horrible vermin” instead of “a monstrous vermin”! Believe it or not, whole articles have been written about that first sentence! Yes, there is more internal structure, but this is a good start. My guess is that you likely did not read the Reed-Kellogg version in its entirety, in spite of the colors, which means nothing. The version above however is simplicity itself.

Not everyone likes to diagram sentences. As NPR suggests, either you love it or you hate it. I tried teaching it to French students once. One student (whose English was impeccable) just could not even start. Look, I said: “can you at least just draw a horizontal line, and then divide that line in the middle with a vertical line - put the subject on one side and the verb on the other?” He said, "No, I can't". Really? He just wouldn't do it! It's not that he couldn't, but rather that he wouldn't. The other student (whose English was a bit sketchy) - his friend - just loved it and went to town with it!

(It's interesting to note that Reed and Kellogg were teachers at the polytechnic institute, which suggests an engineering background. Indeed, I rather think that sentence diagramming has more appeal to "gearheads" than others.)

It would be premature to say that it is a "lost" art since interest in it is still simmering as can easily be seen on the internet. My interest then is to help revive this "fading art" by tweaking it a little bit by simplifying an aspect of it and augmenting another. Forget the fancy crooked lines or the slanted lines; don't try to write on slanted lines. And don't agonize over gerunds and participles. Just boxes and arrows. That's it - just boxes and arrows. The Boxes can be as big or small as you need to make them, and as fits the style of the students. Boxes can be placed higher or lower than others, relative to their functional roles. The arrows flow naturally from the function of the words. Adjectives modify words, hence the arrow points to the word it modifies. A subject points to the verb, and the verb points to the object (assuming it is a transitive verb). A linking verb has two arrows pointing to it since that implies its function, namely to link a subject with some other thing.

The original intention was certainly a good one, but, to my way of thinking there is an easier way to do the same thing that conveys a similar message without having to overthink it or overmap it (not officially a word!). There's no reason to graphically capture every nuance between a gerund and a participle and an infinitive with what amount to stick figures! But sentence diagrams have a place. Let me show you.

That’s the Flat Irons, where I used to go hiking, in Colorado when I went the University there. That’s a bison in the foreground, also known as a buffalo (“Go Buffs!”). They’re actually pretty aggressive bullying critters, known to buffalo others in their massive herds of buffalo (yes, that’s also the plural). They ranged far and wide in the American West. From across the plains in Colorado, all the way to Buffalo, New York.

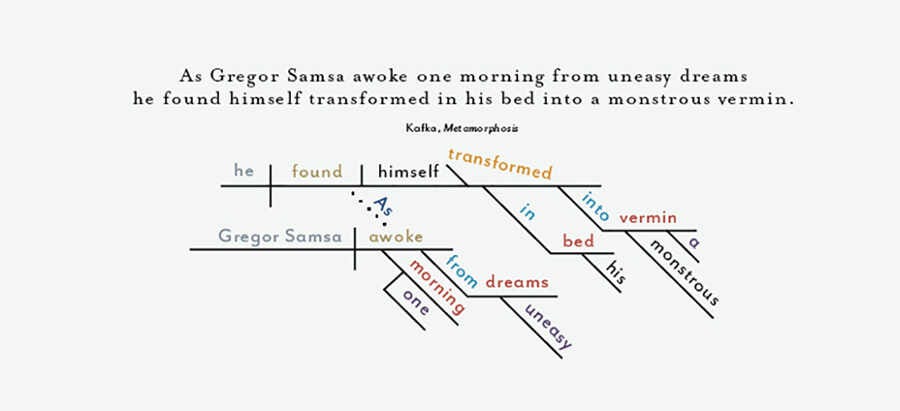

There you have it: a proper name, a noun (plural and singular the same), and a verb. Which brings me to this: did you know that:

Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo.

Can you diagram that sentence? Yes, it’s grammatically correct (whole articles have been written about it!)

Here’s a simpler version to get you started:

Or more simply:

Your homework: where does the remaining “buffalo Buffalo buffalo” go?

Who Said ‘Yes, We Can’ First? This Content Was Published at https://collive.com/who-said-yes-we-can-first/